French postcards 4

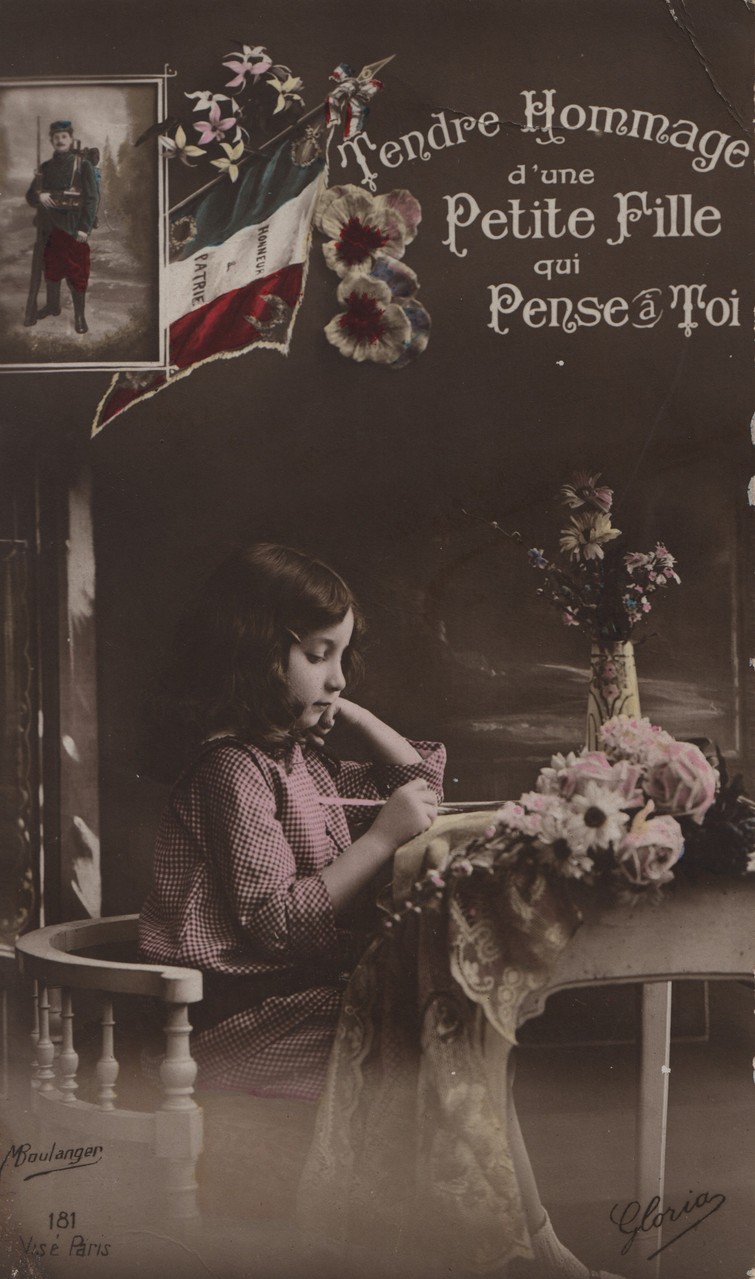

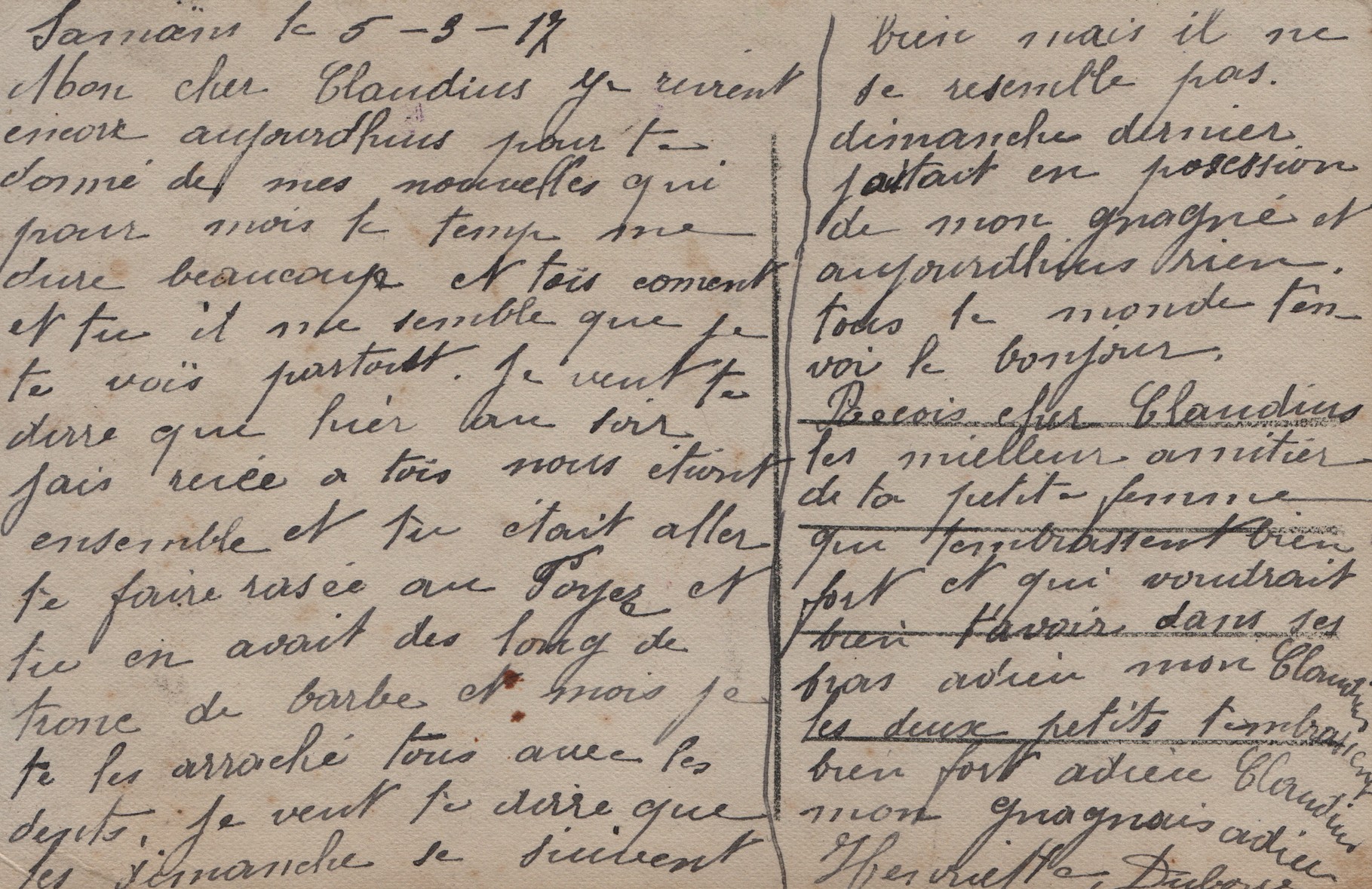

Postcard 1:

Nouzières Sunday 23 August 1914

My little friend

Today I have not received anything yet. There are a lot at Dissais like that. I am pretty sure that you write to me every day. But I am imagining that you may be ill. You cannot know what is happening because it is so far. Never mind, have courage my dear friend. Yvette is feeling a lot better. Everybody is well and we wish that you are the same. I kiss you a thousand times my good Camille. Your wife who loves you and does not forget you.

Translator's note:

Notes: “There are a lot at Dissais like that”

My guess is that Léa thinks that some cards from her husband must have got lost or gone to someone else called Dissais or maybe are piling up in the town of Dissais, a very common family name in Poitou Charentes but also a common place name.

Symbolism: There is no legend on this card but the flowers clearly send a message: “pensées”, the French word for “pansies” is the same as the word for “thoughts”. This explains why the pansy is often found on these WW1 postcards.

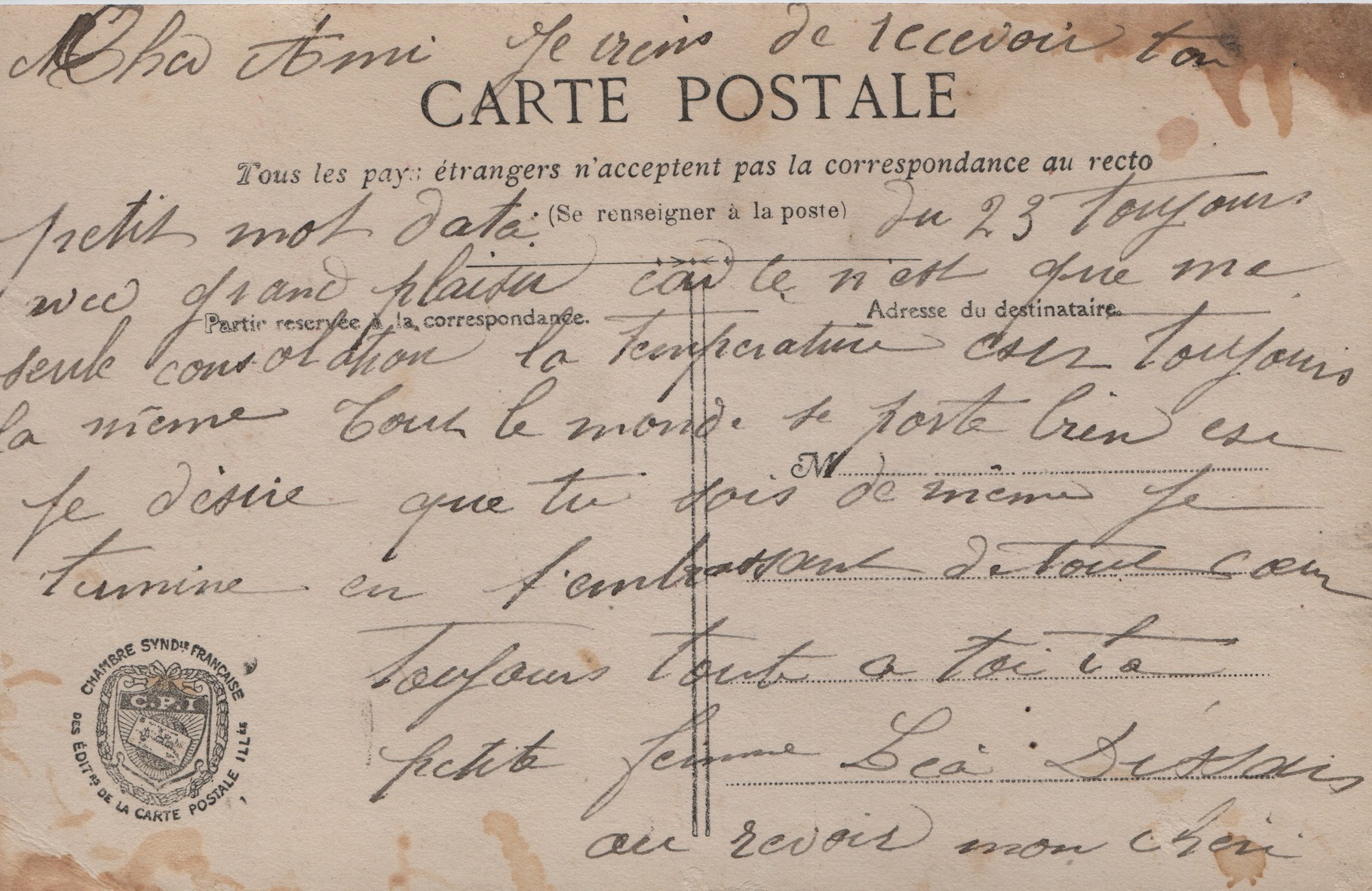

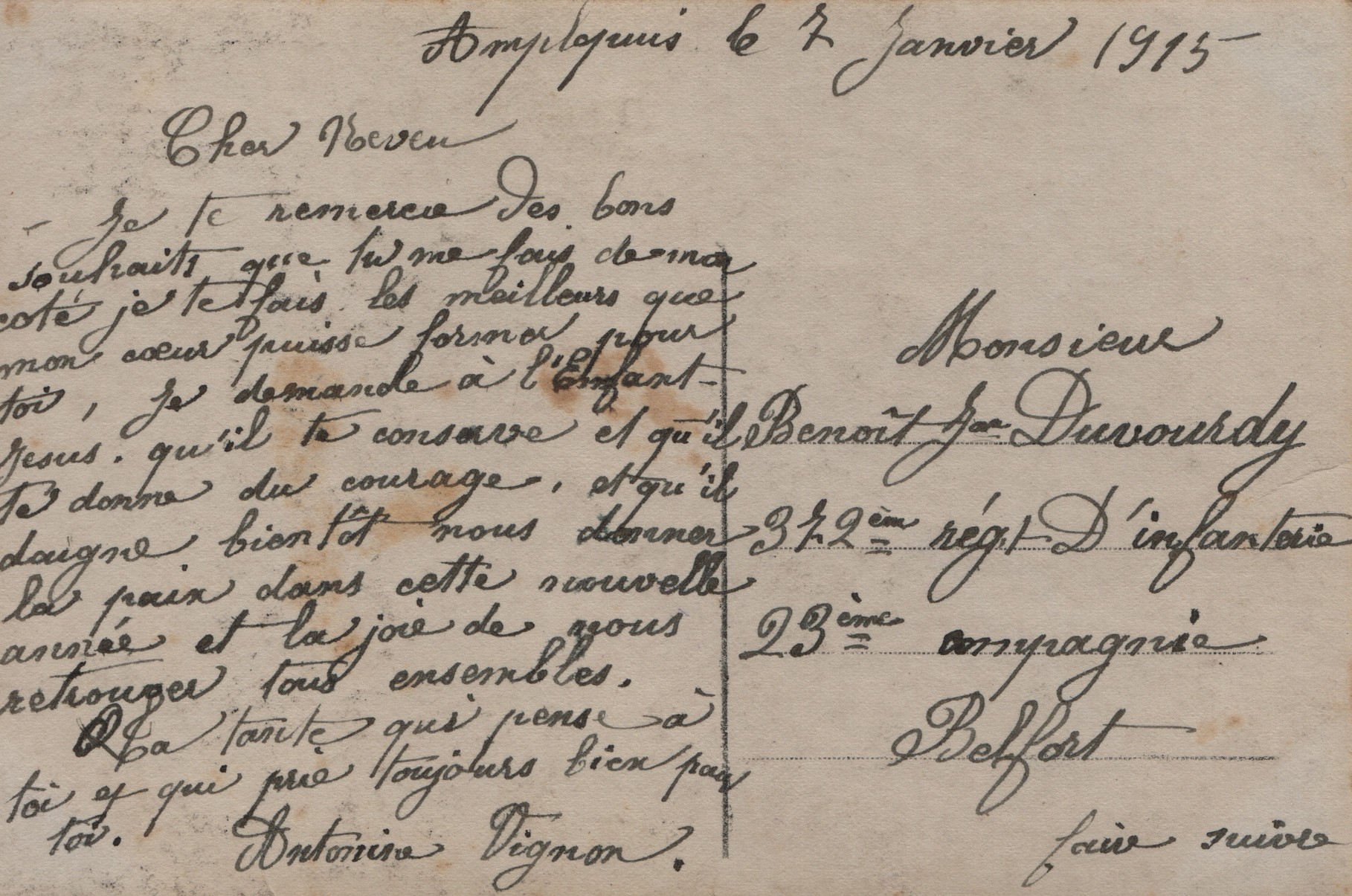

Postcard 2:

Legend:

Loving is living: let me on your shoulder taste this precious happiness, feel my soul fly high in your silent kiss.

Message: Nouzières 11 May 1916

My dear Camille,

I have just received your kind letter of the 7th. I am always happy (to read you) although I understand that you haven’t got much entertainment but the most important is that you are not in danger. I can assure you that I don’t have much entertainment either. I can’t stop laughing when I read your little words; I’d like to see you do the cooking but I am sure that you do it well and that these Messieurs are happy. If you come back to me, it is always the way I put it (if) as I am always scared, you will be able to say that you have done a bit of everything. If I were patient, as some (women) are, I would think of myself as one of the happy ones in spite of all this misery but as I can’t find pleasure in anything…

Translator's note: Camille was originally in the cavalry but for some reason he was no longer able to ride and was moved to work in the kitchen of the Etat Major as a cook. His wife thinks this is funny. My guess is that he probably never did the cooking at home! She teases him in a lovely way but also encourages him. A wonderful touch in this letter that shows that men (as well as women) had to adapt to all sorts of new roles!

French

Nouzières le 11 mai 1916

Mon cher Camille

Je viens de recevoir ton aimable carte du 7 toujours contente malgré que je crois bien que la distraction n’est pas belle mais le principale c’est que tu ne sois pas en danger. Je t’assure que moi non plus j’en est pas de distraction. Je ne peux m’empêcher de rire en lisant tes petits mots car je vouderai bien te voir a faire ta cuisine mais je suis bien certaine que tu le fais bien et que ses Messieurs sont contents en effet si tu reviens c’est toujours le mot que j’emploie car j’ai toujours peur tu pourras dire que tu auras fait de tout un peu si j’avais une patience comme il y en a je me trouverai une des heureuses malgré la misère mais comme je n’ai jamais rien qui me fait plaisir. Je te quitte donc pour aujourd’hui il fait beau temps ta femme qui t’embrasse bien fort et qui pense toujours à toi. Léa Dissais

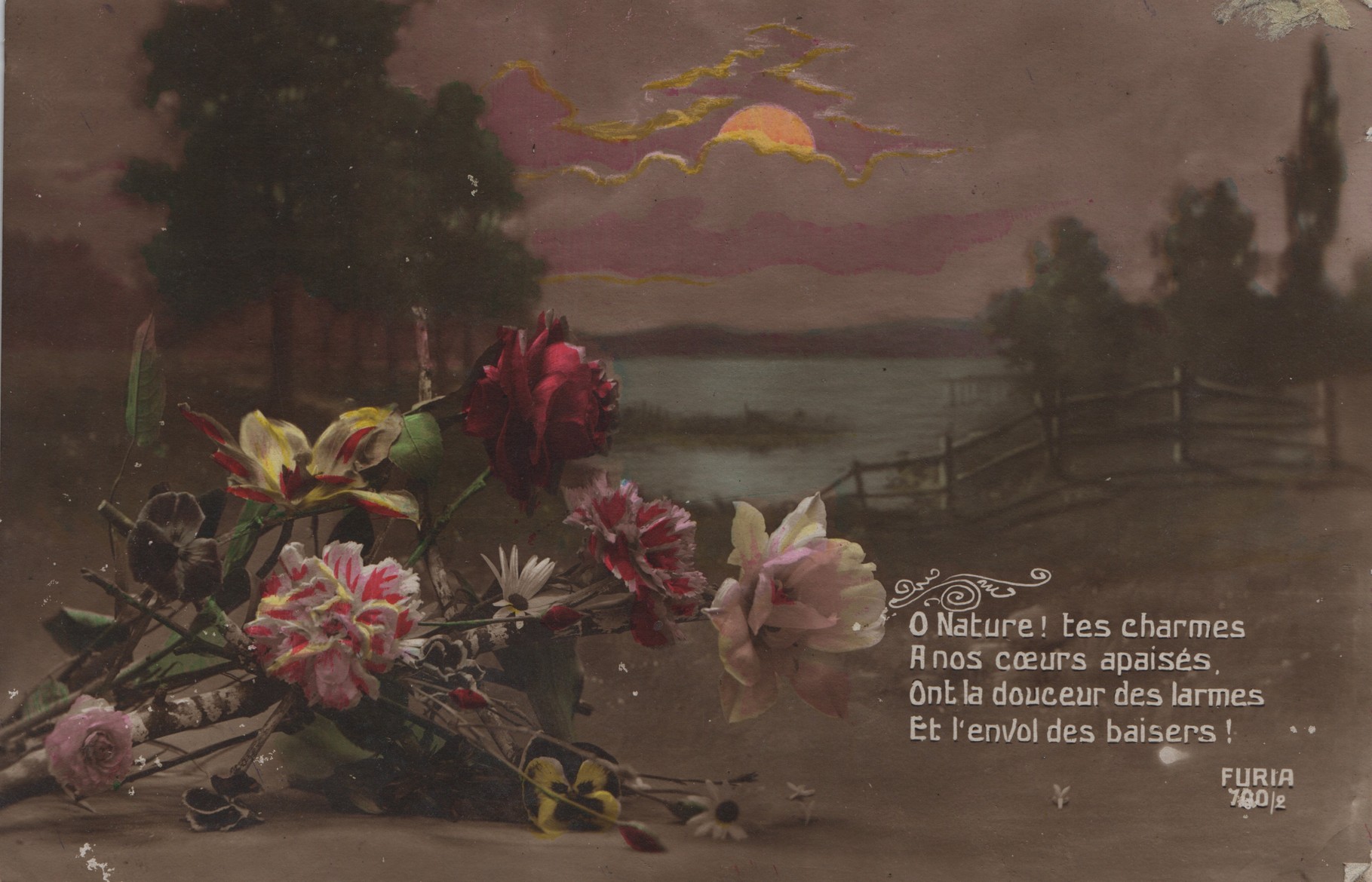

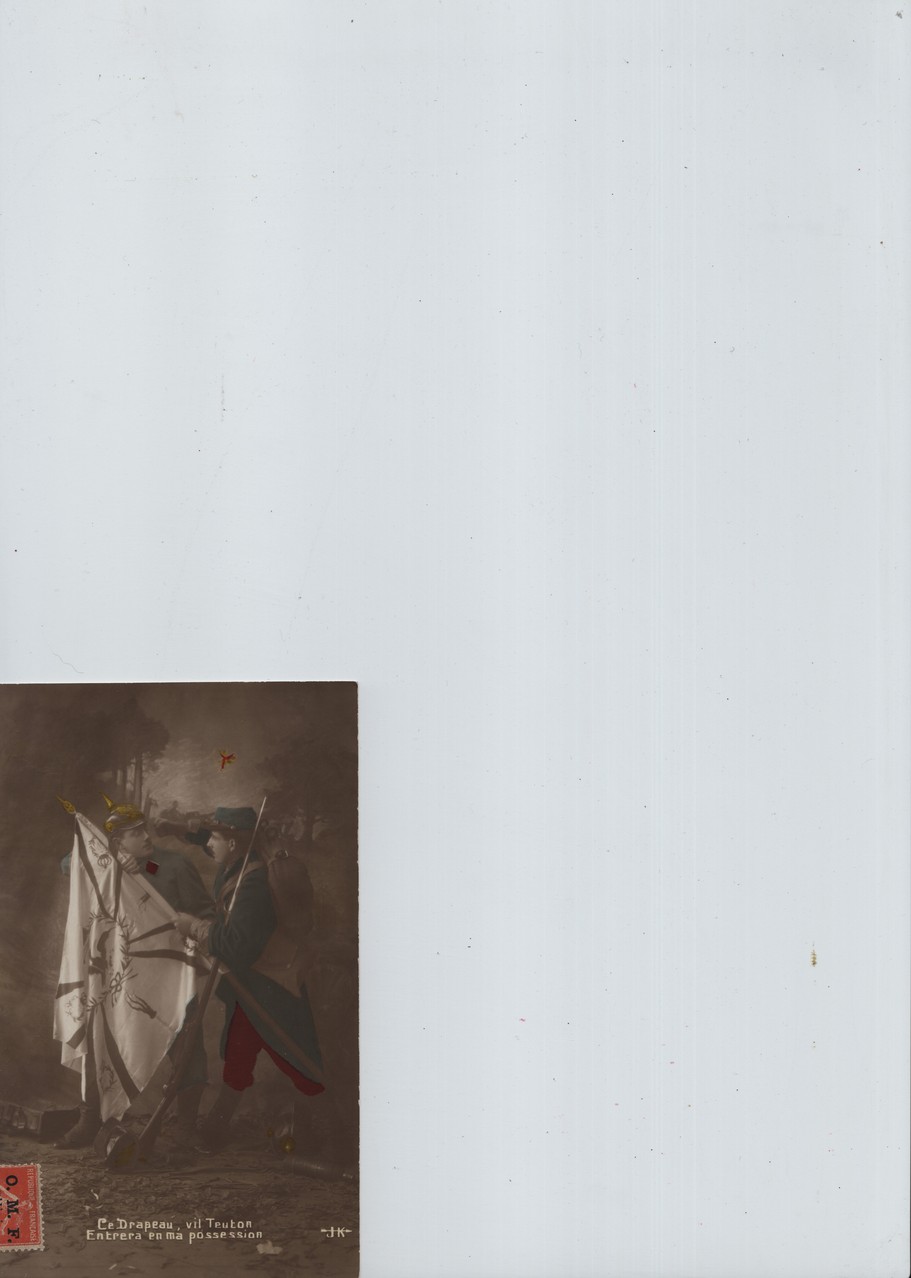

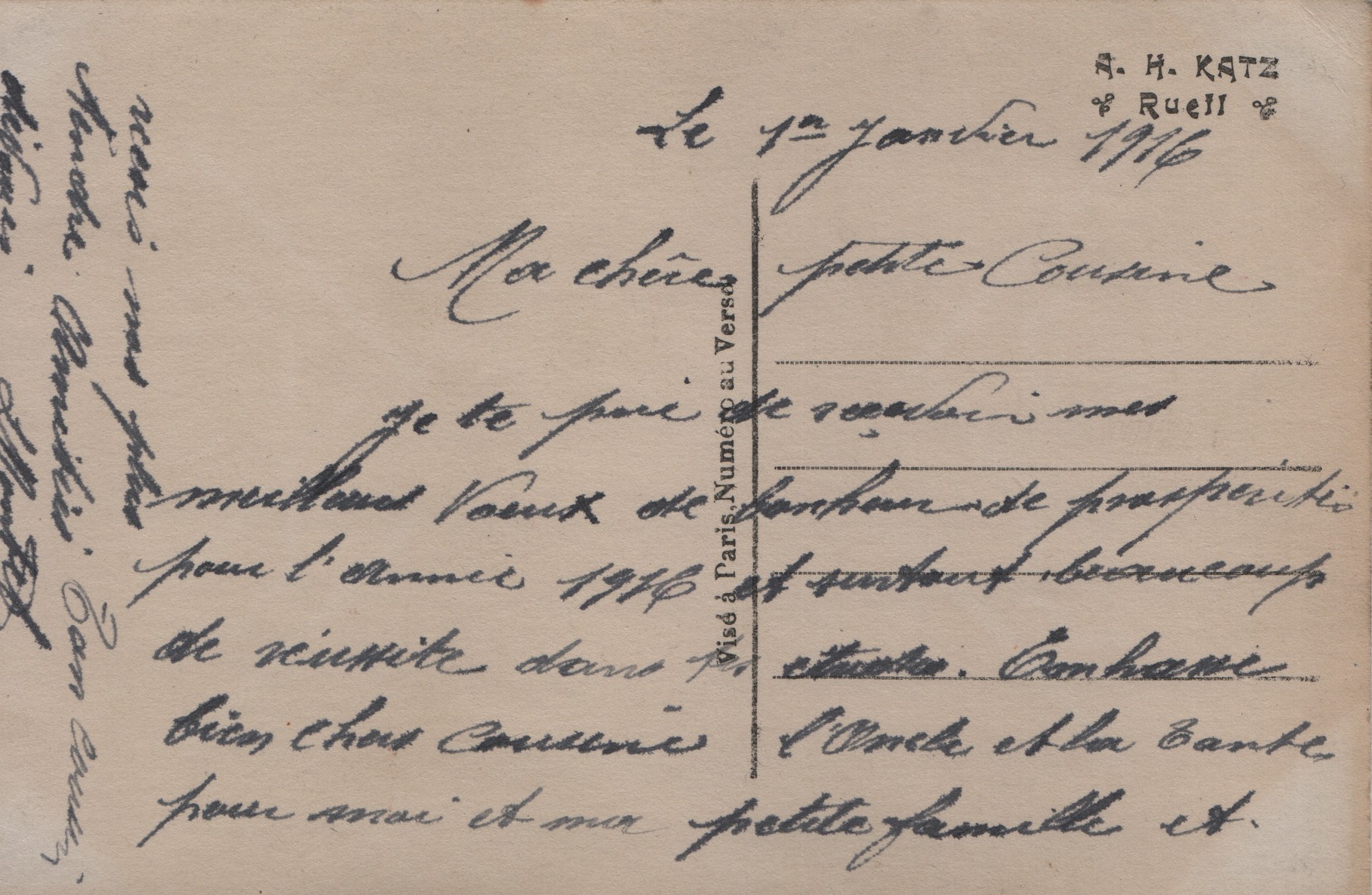

Postcard 3:

Legend: O nature! Your charms to our peaceful hearts have the sweetness of tears and the flying lightness of kisses

Message:

Nouzières 8 Juin 1917

My little friend,

I have received with pleasure your good card of the 5th. So I’ve had the medical check up. The major told me that my heart was beating an extra 5 seconds every 10 minutes. Now I don’t know what will happen; that’s all he told me. Marguerite Pignoux from Marignef was behind me. I don’t think that she was accepted either. I’ve had enough. The market was very good. I sold my eggs 2,50 fr and the butter 4fr.

I think my darling that there is a big great mess; and it’s everywhere. It can’t be worse. My only consolation is to re-read that you will not forget me for one minute.

Receive a thousand kisses and [can’t see the end on scanned copy]

Notes: Léa has a medical with an army doctor. The reason is unclear. She is “not accepted”, she writes. Is she trying to get some sort of position within the army or is she trying to qualify for some extra benefits? It is difficult to say.

The “big great mess everywhere” mentioned by Léa is probably a reference to the general upheaval that shakes France in the spring and summer of 1917: social unrest all across France with strikes

in factories and work places, mutinies in the trenches. This is also a period of intensification of battles in the north of France. There is a feeling of general chaos which is well reflected in

this postcard. The war has lasted too long. The French, both civilians and militaries have had enough.

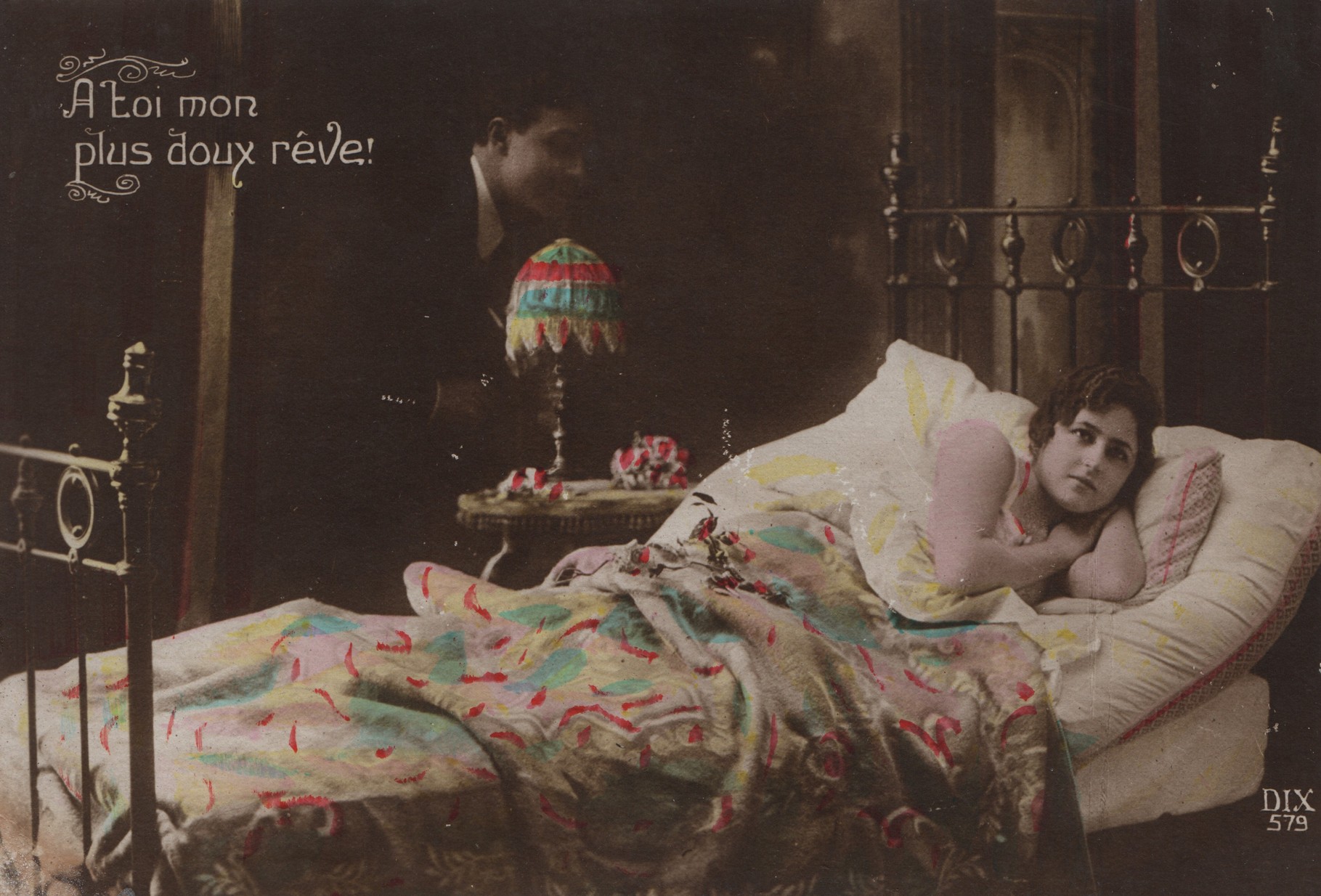

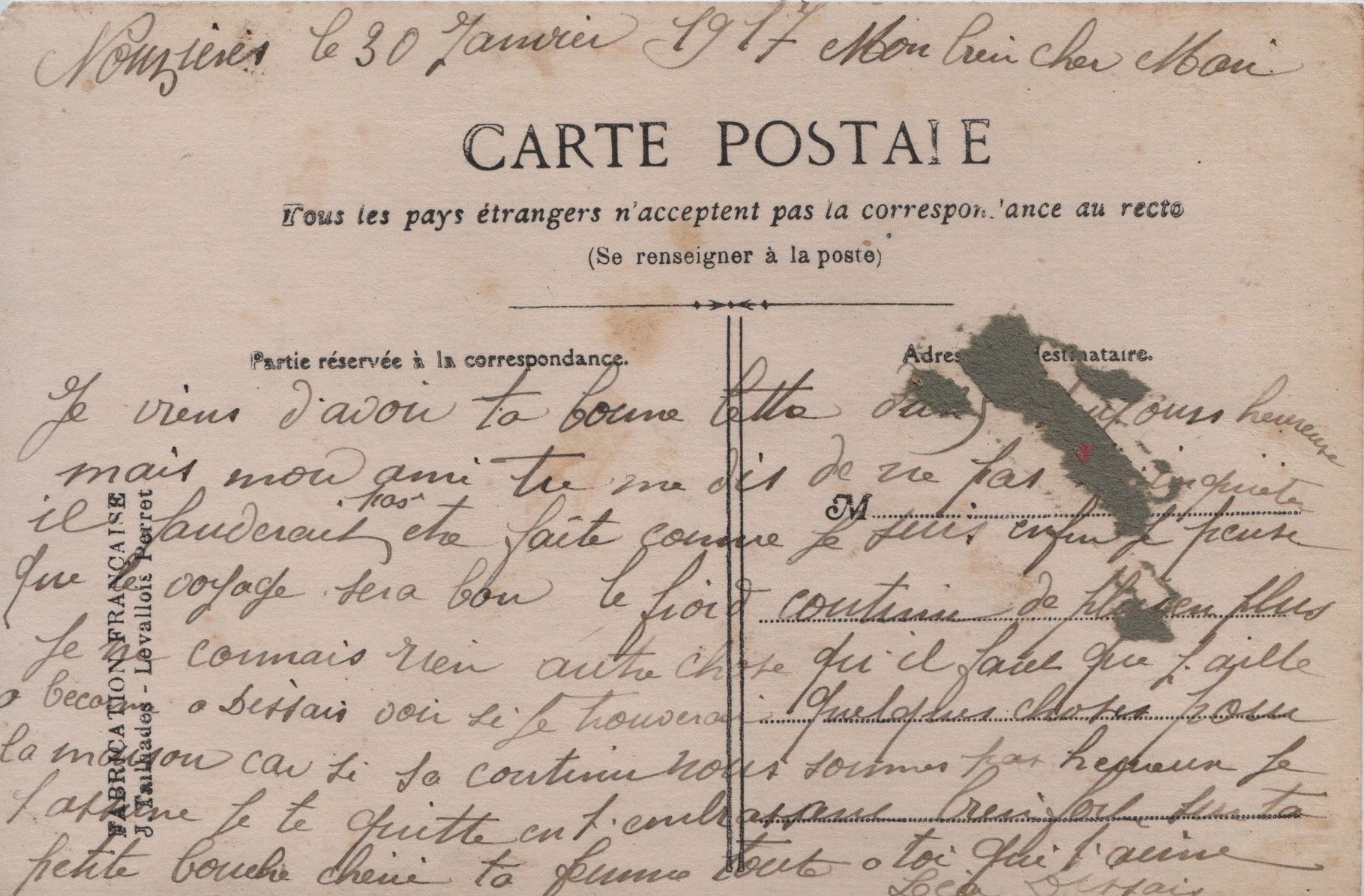

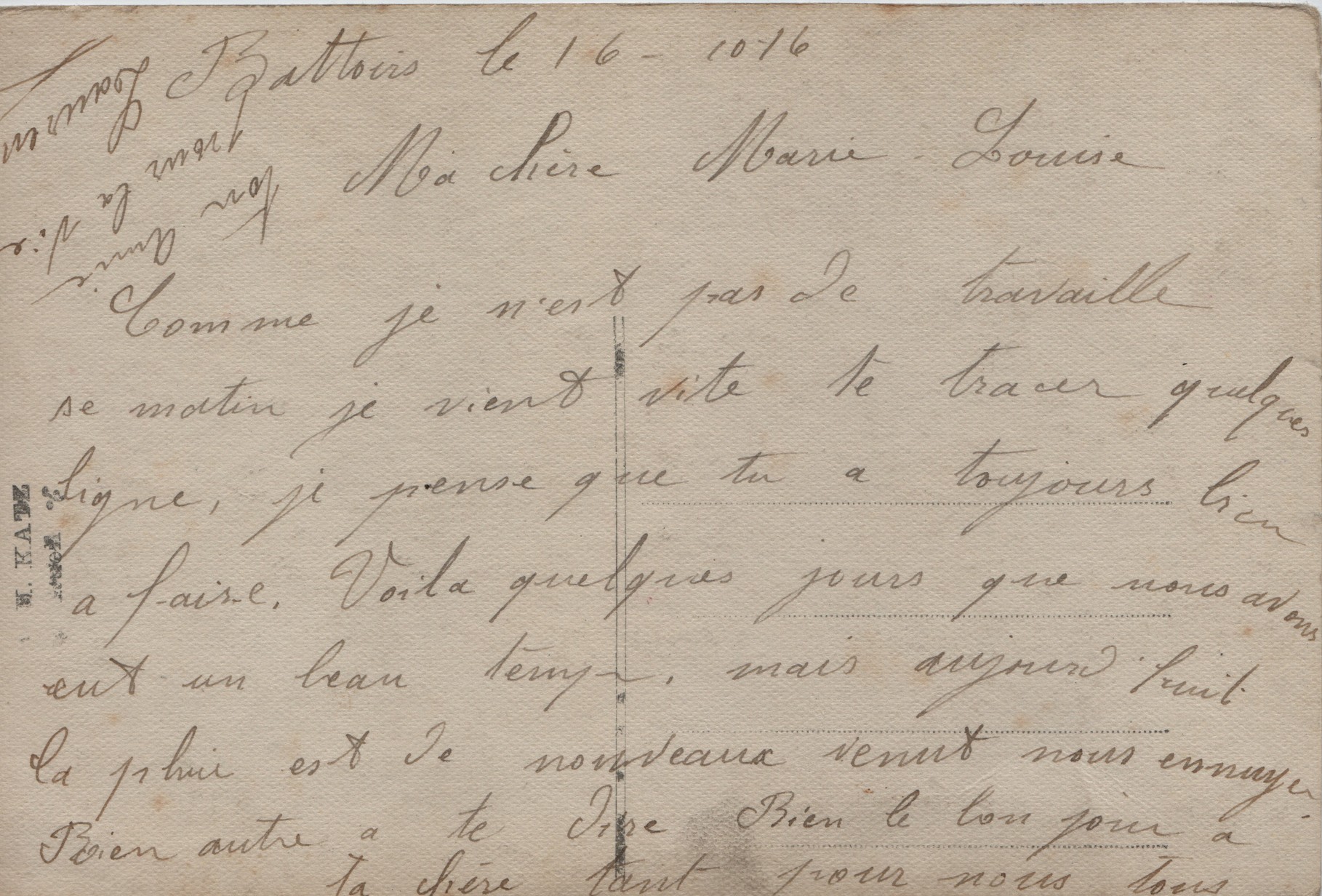

Postcard 4:

Legend:

To you my sweetest dream

Message: Nouzières 8 February 1917

I have just received you card of 31st, always a pleasure. I am spending this Sunday as usual. I have just been to the town hall to have my name put down for the sugar card. I don’t know what will come of it. One has to wait for the maintenance books (ration books) from the prefecture (departmental office). It was hard to hold the direction of the bécane (word for bicycle) because the frost is dreadful. They say that it’s like 79. I have never been so cold and there is only green wood to burn, apricot trees, peach trees from Guignier and vines. There are nearly all burnt. I so miss you being so far way. I am going to leave you by kissing you. With all the friendship of my heart.

Your Léa

Translator's note: On the severity of the winter of 1879 see http://www.meteopassion.com/decembre-1879.php

Temperatures of up to minus 33 were registered in Langres. Paris was covered in more than 25 cm of snow and the Seine was frozen. The painter Monet was fascinated by this extreme unusual weather and famously painted many frozen lanscapes.

In 1917 the last days of January and the first two weeks of February bore a close resemblance to the winter of 1879 with extreme temperatures of

minus 15 in Paris and minus 20 in Grenoble. Rivers again were frozen. See http://www.alertes-meteo.com/vague_de_froid/hiver-1900-1950.php

This added to the general hardship of the population and the feeling of misery.

On food rationing see http://www.nithart.com/fr14-18.htm

Severe rationing starts in 1917 around the time when Léa writes this postcard. This explains why she says that she had to put her name down for the “sugar card”. This is a new system which is

being put in place. She is unsure of the whole process. Sugar was rationed to 750gr per month for adults and you were not allowed to make cakes.

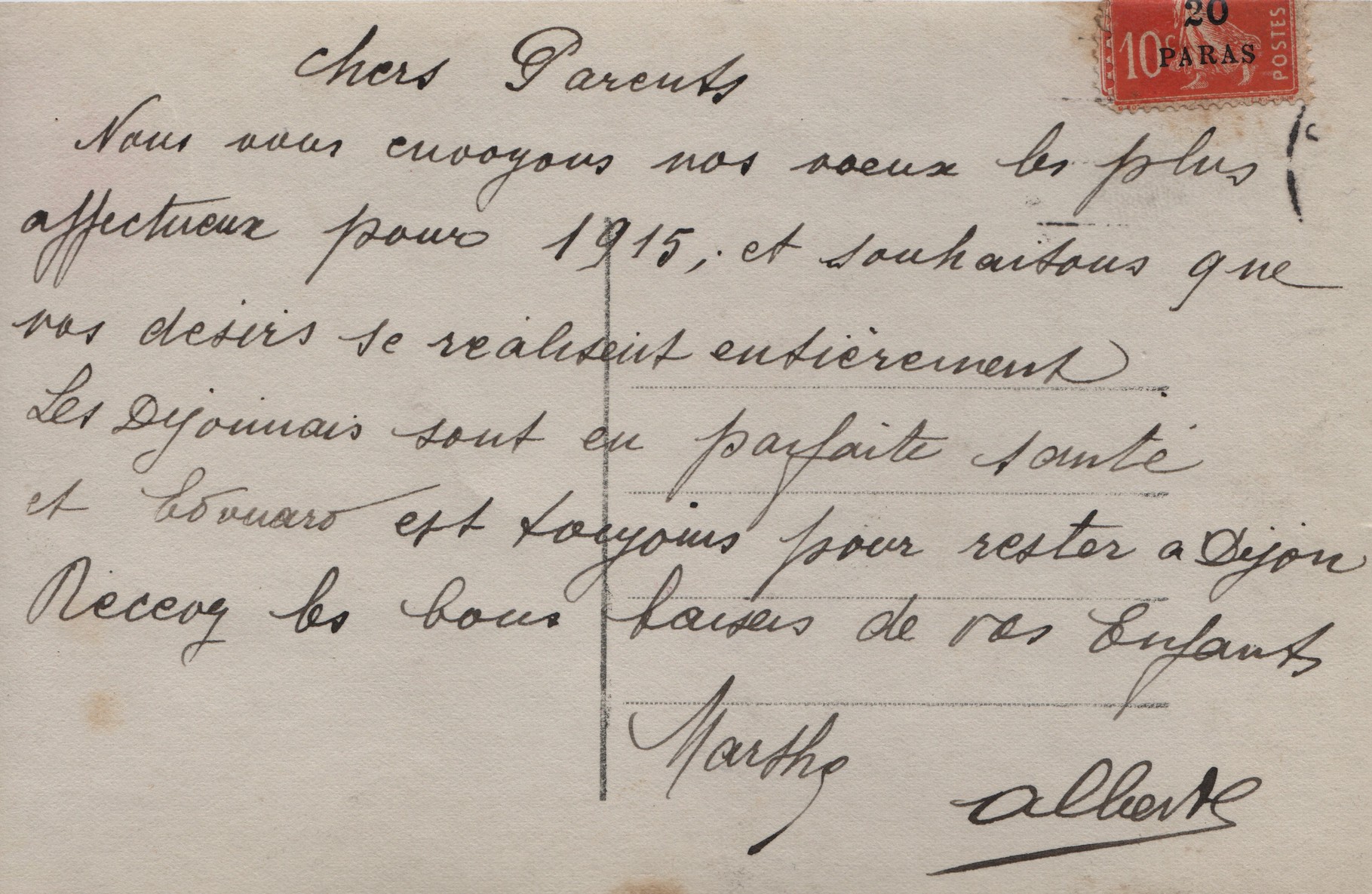

Postcard 5:

Legend: Be always valiant, serve your mother land well. She is a dear mother to both of us.

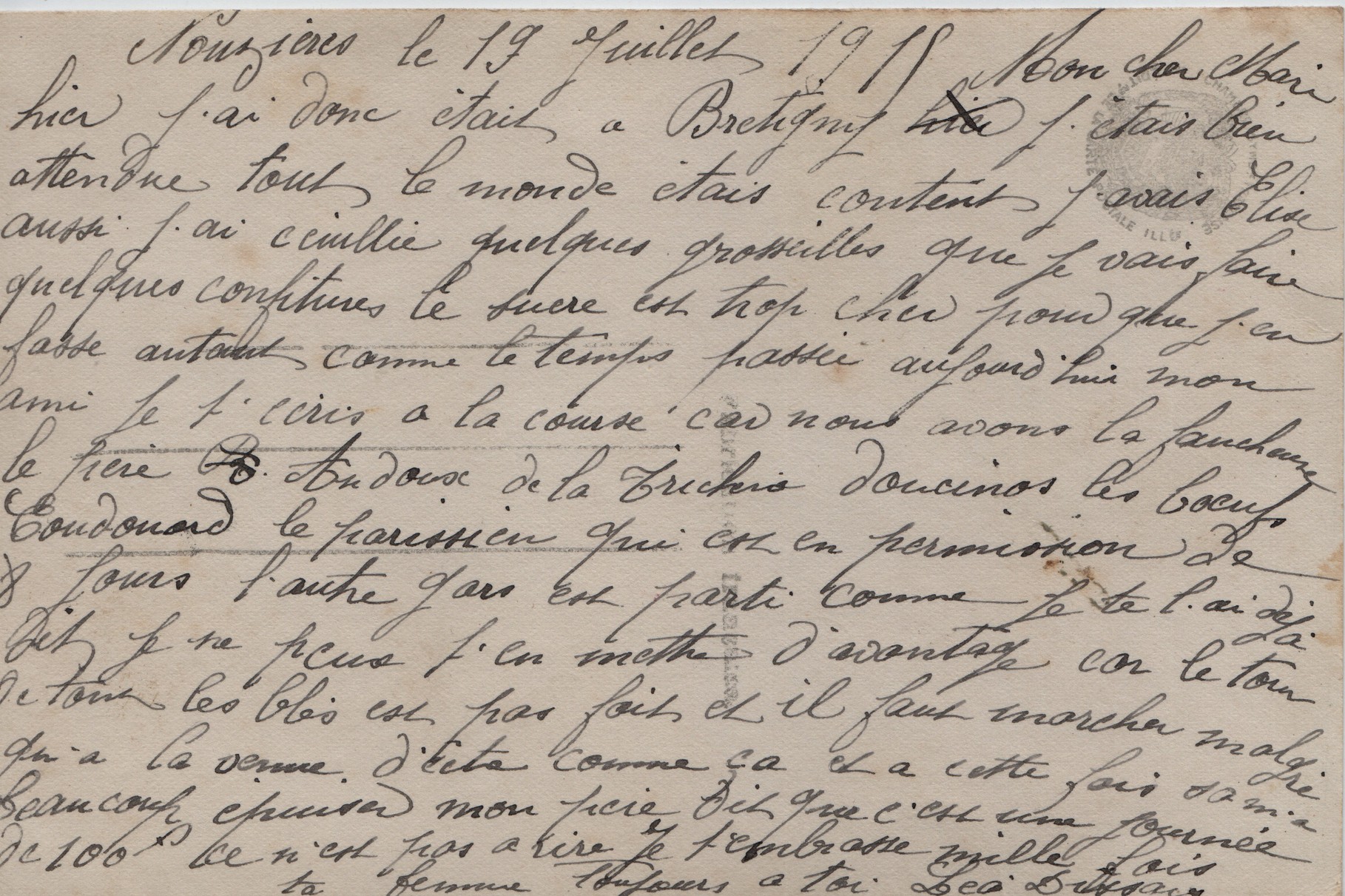

Message: Nouzières 19 July 1915

My dear husband,

Yesterday I was in Bretigny. They were waiting for me; everybody was pleased. I also had Elise. I picked some redcurrants to make jam. The sugar is too expensive to make as much [jam] as I used to do. I am writing to you in a hurry as we have the threshing machine, the brother Audoux from the Trichis […] the oxes. Edouard the Parisian is on leave for 8 days. The other guy has gone as I have already told you. Can’t say more as the hay is not finished; one has to walk a lot and this time this has exhausted me completely. My father says that’s a day worth 100 francs. It’s no laughing matter. I kiss you a thousand times. Your wife all yours.

Léa Dissais

Translator's note: Redcurrant jam is one of the most popular preserves in rural France. It is actually a sweet set jelly and is consumed with bread and butter. By 1915 sugar had

already become scarce and prices had gone up dramatically. Up to the time of Napoleon, France relied mostly on cane sugar imported from the colonies. Napoleon encouraged the production of local

sugar through the cultivation of sugar beets. By 1814 the sugar beet was cultivated all over France (but especially in the North and the Somme area) and the country had more than 200 active sugar

plants that transformed beets into sugar for the local population to consume. One of the main reasons for the decline of the sugar production during the first world war is the destruction of

sugar plants in the Somme area. Postcards showing the ravages of the war can be seen on the website of the Syndicat National des Fabricants de Sucre (the French National Syndicate of Sugar

Producers): http://www.snfs.fr/site/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=72&Itemid=132

Although French rural population was lucky to enjoy food from their holdings, storing the supplies was an issue because natural preserving ingredients such as sugar were expensive and difficult to obtain.

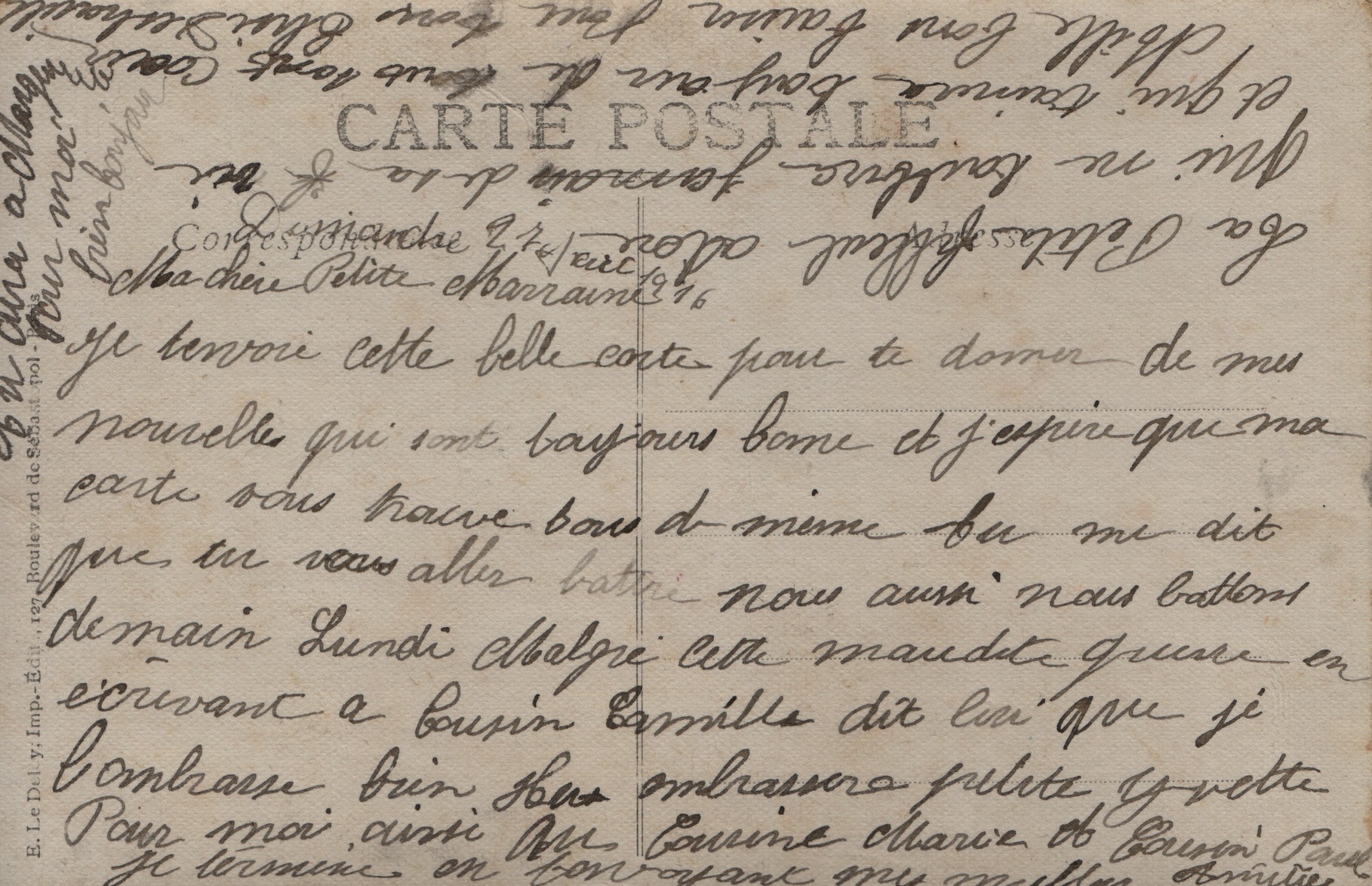

Postcard 7:

Legend: I sometimes dream that in some hidden retreat, in the tender nest that I would have sought, we would be hiding far away our joyful hearts; one loves with greater depth in a hidden place; this is where I would live my sweetest moments…

Message:

Nouzières 30th January 1917

My very dear husband,

I have just received your good letter- always happy to do so. But my friend, you tell me not to worry; that’s just in my nature. Never mind I think that the journey will be good. The cold continues, even worse. I can’t think of anything else [to say] other than that I need to go to Dissais on my bike to see whether I can find something for the house. If that continues we won’t be happy, I can assure you. I leave you by kissing you very warmly on your little darling mouth.

Your wife, all yours, who loves you.

Léa Dissais